Abu Simbel

The Temple That Moved Mountains

The approach begins quietly.

A curved path leads around the edge of Lake Nasser, bordered on one side by still blue water, and on the other by a low, artificial mountain—shaped not by nature, but by design. It hides the temple from view, at least at first. There are no signs or grand gates. Just the sound of footsteps, the glare of the sun, and the slow bend of the road.

Then, just beyond the final curve, the temple appears.

The façade of Abu Simbel rises from the rock with almost no warning—four seated statues of Ramses II, each over twenty meters tall, carved directly into the cliff. They look out toward the rising sun, faces calm, symmetrical, commanding. It’s not just their size that leaves an impression, but their presence. The temple doesn’t introduce itself. It reveals itself.

The impact is immediate.

Standing beneath them, the scale becomes impossible to ignore. The fingers of the statues are longer than a person is tall. At their feet are smaller figures—wives, children, gods—positioned with intention, part of the pharaoh’s carefully constructed image. Above the entrance, the falcon-headed sun god Ra-Horakhty stands in a central niche, carved in high relief.

Every part of the temple's façade sends a message: this king was powerful, chosen by the gods, and meant to be remembered.

Inside, the temperature drops. The great hall is lined with massive pillars shaped like Ramses himself, arms crossed in the pose of Osiris. Between them, scenes from the pharaoh’s life unfold across the walls—military victories, religious rituals, offerings to the gods. Ramses at Kadesh. Ramses among the deities. Ramses in eternal command.

Experience it

Abu Simbel was never meant to be hidden.

Built in the 13th century BCE, at the height of Egypt’s New Kingdom, the temple was carved into a sandstone cliff overlooking the Nile in Nubia, near the ancient border with modern-day Sudan. Its purpose was more than religious—it was political. This temple marked the southern reach of Ramses II’s empire, a bold declaration of power to all who entered from the south. It was meant to impress, intimidate, and endure.

But Ramses did not build Abu Simbel simply to be seen. He built it to interact with the sun, and by extension, the gods.

At the very heart of the temple, behind the halls and colossal statues, lies a sanctuary—small, solemn, and deeply symbolic. Seated against the back wall are four figures: Ptah, god of creation and the underworld; Amun-Ra, king of the gods; Ra-Horakhty, god of the rising sun; and Ramses II, immortalized among them.

Twice a year—once in February and once in October—something remarkable happens.

At sunrise on these two days, a beam of light enters the temple. It passes through the main hall and reaches the sanctuary, where it strikes the faces of the statues. Three of them are illuminated: Amun-Ra, Ra-Horakhty, and Ramses II. Ptah remains in shadow. Always.

This detail is not an accident. It’s a feat of astronomical precision, achieved with tools and knowledge over 3,000 years ago. The alignment is believed to correspond to two of the most important dates in the pharaoh’s life: his birthday and his coronation. The sunlight touches the king’s face as if to renew his divinity, to bless his rule even beyond death.

But Ptah, god of darkness, was never meant to be touched by light. In ancient Egyptian belief, Ptah ruled the hidden realm—the source of creation, the mysteries of the underworld, and the forces that existed before the sun itself. To shine daylight on him would defy his nature. So, even in the moment of perfect illumination, he remains cloaked in shadow—eternal, unseen, and untouched.

It is one of the most subtle and powerful expressions of ancient theology written into stone. Not a word is spoken, yet the architecture teaches.

Today, visitors still gather before sunrise to witness this event. The light travels across nearly sixty meters of stone and lands, briefly, where it was always meant to. Though the temple no longer stands in its original location, the alignment remains almost exact—off by only one day.

Abu Simbel, as it is seen today, is not where it was originally built.

Experience it

In the early 1960s, the world was changing, and so was the Nile.

Egypt had begun construction of the Aswan High Dam—an ambitious project designed to control the river’s flooding, generate electricity, and secure water for generations to come. But behind its walls, the newly forming Lake Nasser would rise, slowly and steadily, until it swallowed entire valleys of southern Egypt and northern Sudan.

Among the ancient sites in its path was Abu Simbel.

The temple, carved into the cliffs of Nubia over three thousand years ago, stood directly in the flood zone. Without intervention, it would vanish beneath the waters—along with over a dozen other monuments from the era of the pharaohs.

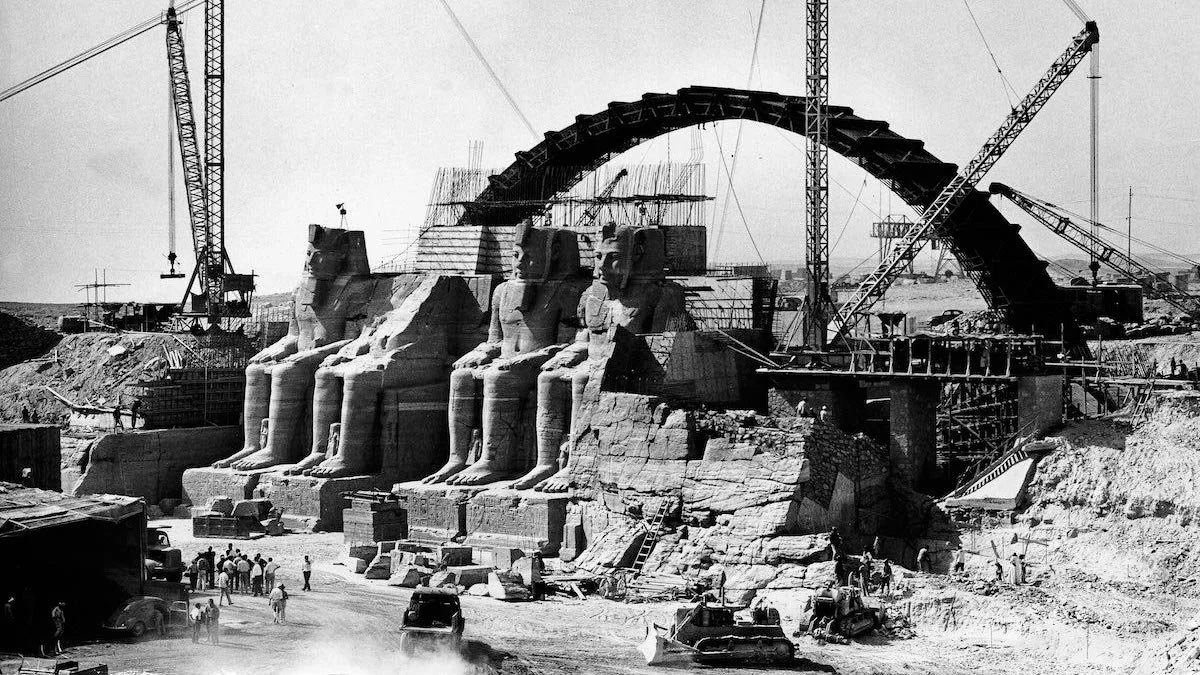

And so, in 1960, an unprecedented international campaign began.

Under the guidance of UNESCO, engineers, archaeologists, architects, and craftsmen from around the world came together in a mission that was equal parts excavation and resurrection. It was not enough to simply preserve the artwork or copy the temple elsewhere. The original had to be saved. In full. In place. In spirit.

The cliffs were carefully mapped. Every block of stone—over 1,000 pieces, some weighing up to 30 tons—was cut, labeled, and moved, one by one. But the challenge was not only in moving stone. It was in rebuilding a mountain, and doing so with enough precision to preserve the temple’s most sacred feature: its solar alignment.

The new site, just 200 meters from the original, was chosen and sculpted to match the natural slope of the cliffs that once framed the temple. A vast artificial dome was constructed inside the hill to support the weight of the monument, hidden behind the stone skin that gives the illusion of natural rock.

In total, the operation took four years—from 1964 to 1968—and cost over $40 million at the time. It remains one of the largest and most ambitious heritage rescue projects ever attempted.

And it worked.

Today, as visitors follow the curved path around the man-made cliff and Abu Simbel comes into view, most have no idea they’re looking at a relocated masterpiece. The illusion is complete. The atmosphere remains intact. And twice a year, the sunlight still travels down the temple’s axis to illuminate the gods—missing by only a single day.

But beyond its engineering marvel, the relocation of Abu Simbel carries another kind of legacy.

It proved that the past could be protected without being frozen. That memory could move forward. And that nations, when united by culture and purpose, could shift more than just stone—they could shift history.

The temple that was nearly drowned is now more than a monument. It is a symbol of what can be preserved when we choose to protect what we inherit. In saving Abu Simbel, the world didn’t just rescue a piece of Egypt. It rescued a piece of itself.

And for those who stand before its colossal gates today, what they see is more than a king’s legacy carved in stone.

They see proof that time does not only destroy. Sometimes, it creates.

We invite you to experience this moment for yourself.

Join our private, curated journeys through Egypt, where expert guides, seamless service, and privileged access bring history to life—one temple, one sunrise, one story at a time.

Abu Simbel awaits.